By Harmen Huigens

Introduction

The MarEA project’s main method to assess maritime archaeological heritage and the threats posed to it is remote sensing – using aerial and satellite imagery to document archaeological sites, their condition, and how they are threatened by natural or anthropogenic processes. Modern high-resolution satellite imagery is now widely available through digital platforms such as Google Earth. Such sources allow us to look at satellite imagery from the last 20 years or so. Sometimes, however, it is important to look further back in time, especially in areas where modern development has considerably changed the coastal landscape and affected its archaeological sites over the last few decades. For the MENA region we can make use of Corona satellite imagery, taken in the 1960s and 70s. Its applications for the MarEA project are discussed in this blog post, through some examples from Yemen’s Red Sea coast.

About Corona imagery

Corona imagery derive from an American spy satellite mission that ran between 1959 and 1972. The Corona program produced panchromatic (black-and-white) photographs of much of the Middle East and North Africa of up to 2 m ground resolution. This imagery was declassified in 1996 and thus became available for archaeological research and heritage purposes (Philip et al. 2002). The imagery is held and made available by the United States Geological Survey and can be obtained for a small fee. Some of the imagery is already freely available. A relevant source in this regard is the Digital Corona Atlas for the Middle East (Casana and Cothren 2013) which can be accessed here: https://corona.cast.uark.edu.

Corona imagery comes in digital strips and is usually not georeferenced or orthorectified. This can be done in most GIS software with relative ease, using established methods (e.g. Casana and Cothren 2008; Ur 2003).

Application

The greatest advantage of Corona imagery lies in its acquisition date, which for many parts of the MENA region lies before the period when modern development considerably altered coastal landscapes. We can therefore use Corona imagery (a) to differentiate between modern and potentially archaeological features by comparing modern imagery with Corona imagery; (b) to document archaeological sites that have disappeared in recent times due to modern development; and (c) to track changes to maritime sites and landscapes over the last 50 years or so and identify the natural and anthropogenic processes associated with them. Here are some examples from Yemen’s southern Red Sea coast (Figure 1) to illustrate these applications:

Figure 1: Study area (red) on the southern Tihama coastal plain of southwest Yemen.

(a) Salt pans; southern Tihama coastal plain

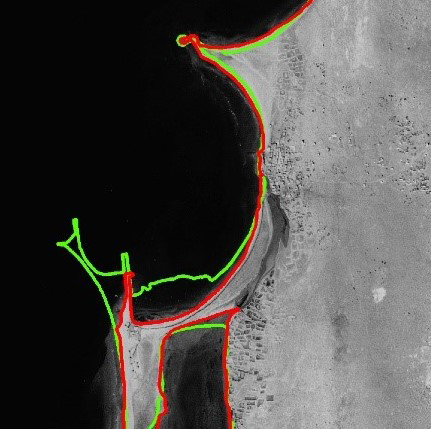

Salt production areas form a significant part of the coastal landscape on the southern Red Sea shore, both in the past and today. To differentiate between modern salt production areas and potentially more ancient ones, we may compare modern satellite imagery with Corona imagery (Figure 2). Here, the Corona imagery shows that the area of salt production was much less extensive than it is today.

Figure 2: Extent (red line) of a salt production area as visible on Corona imagery (left) and modern WorldView satellite imagery (right) in southwest Yemen.

In a similar way we can also identify, for example, pre-modern field systems, settlements and water storage facilities that occur on the coastal plain.

(b) Mokha fortifications

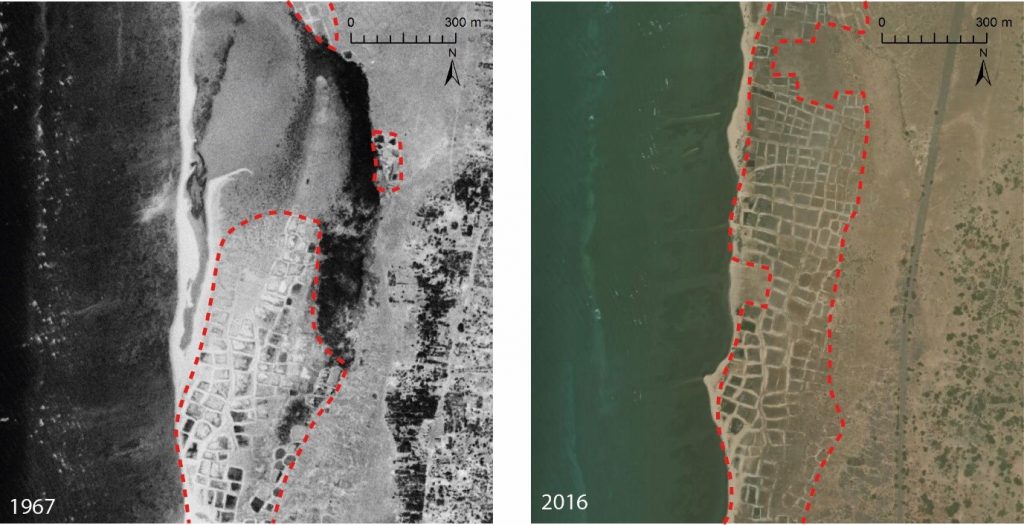

Many archaeological features have unfortunately been damaged or destroyed in recent times along the Red Sea coast due to town, harbour and infrastructure development, and conflict. Corona imagery can help map such features, and the degree to which they have been impacted by comparison with modern satellite imagery. The port town of Mokha, for example – once Yemen’s principal port and a major location for international coffee trade – has been severely impacted in recent decades (Figure 3). Corona imagery shows the remains the town’s ancient fortifications, such as its 16th to 18th century town wall and forts. Comparing these to modern imagery reveals much of this has been severely damaged, by activities such as road construction.

Figure 3: Remains of Mokha town wall as visible on Corona imagery from 1967 (right) and WorldView imagery form 2016 (right), the latter showing damage to the wall through recent road construction (highlighted by yellow lines).

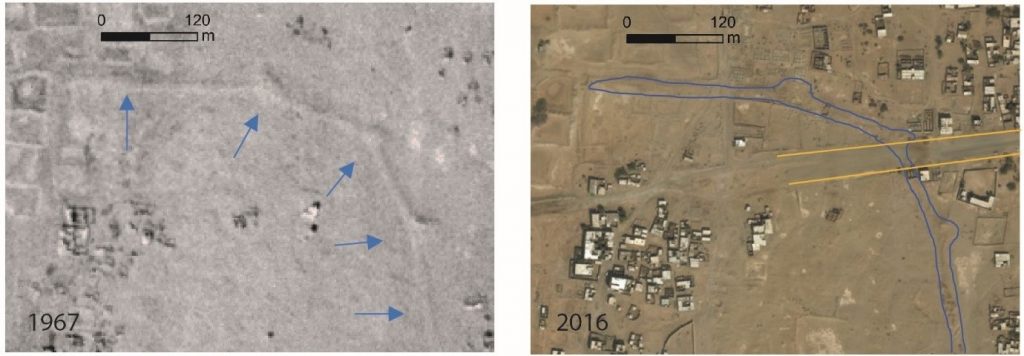

(c) Shoreline development around Mokha

The shoreline around Mokha has been considerably changed over the last 50 years or so, as revealed by Corona imagery (Figure 4). Some areas are affected by natural causes such as erosion and sedimentation due to the action of water currents and waves; other shoreline modifications were largely anthropogenic, such as the expansion of the modern port at Mokha; in some areas natural processes were amplified by human-induced changes. For example, Figure 4 shows an area (c) where the construction of breakwaters has triggered natural sedimentation and erosion processes on either side of these protrusions.

The MarEA project continues to document development of the maritime archaeological landscape, comparing modern satellite imagery with Corona and other ‘historical’ datasets, over the coming years.

Bibliography

Casana, J. and J. Cothren 2008. Stereo analysis, DEM extraction and orthorectification of CORONA satellite imagery: archaeological applications from the Near East. Antiquity 82:732-749.

Casana, J. and J Cothren 2013. The CORONA Atlas Project: Orthorectification of CORONA Satellite Imagery and Regional-Scale Archaeological Exploration in the Near East, in D.C. Comer and M.J. Harrower, Mapping Archaeological Landscapes from Space. New York: Springer, pp. 33-43.

Philip, G., D.N.M. Donoghue, A.R. Beck and N. Galiatsatos 2002. CORONA satellite photography: an archaeological application from the Middle East. Antiquity 76: 109-118.

Ur, J. 2003. CORONA Satellite Photography and Ancient Road Networks: A Northern Mesopotamian Case Study. Antiquity 77: 102-115.

Imagery sources:

Corona imagery: United States Geological Survey (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/)

WorldView3: DigitalGlobe / Esri