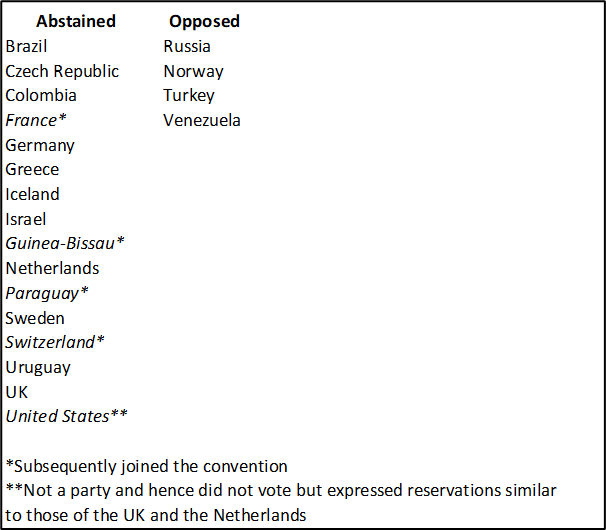

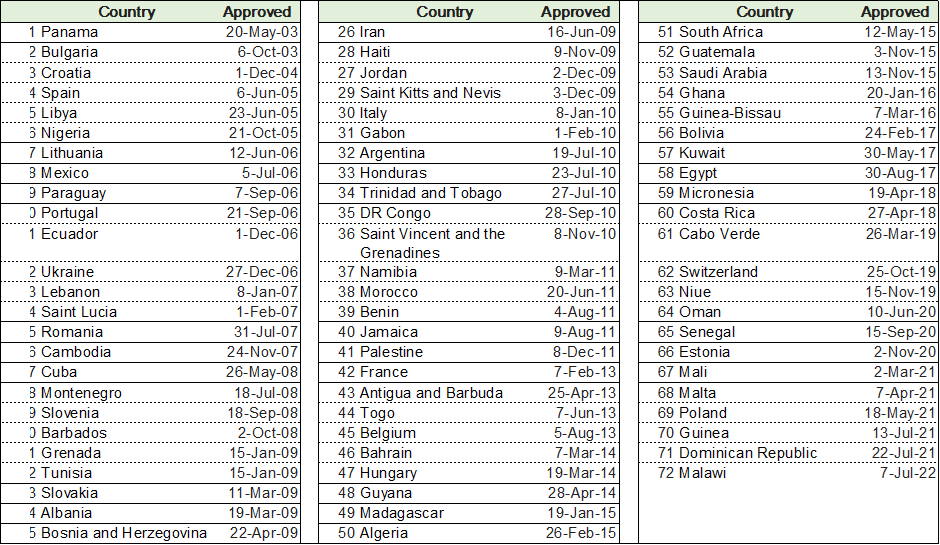

The 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) marked a momentous culmination of decades of negotiation among the community of nations. The vote was overwhelming, with eighty-seven votes in favour, four against, and fifteen abstentions (fig.1). Yet, the more than two decades since has been a slow roll. The Convention only came into force on January 2, 2009, nearly a decade after its passage, and just twenty countries that had ratified it up until October 2008 were parties. As of July 2023, that number has jumped to 72 (fig. 2). Moreover, many of the terms and clauses governing crucial issues such as ownership and decision rights were left deliberately vague to avoid crossing red lines separating opposing camps in the debate and to allow for negotiation and gradual consensus-building during the actual application of the Convention (Dromgoole, 2013, pp.52-63). As there is no centralized enforcement mechanism built into the treaty, much is left in the hands of national court systems. Ominously, the key dividing line in all matters maritime is between coastal states and flag states (i.e. maritime powers), and nearly all the key players in the latter camp declined to support the Convention (Dromgoole, 2013, p.55). Notably, multiple former colonies rich in colonial-era shipwrecks, particularly in the Americas, also joined the flag states in opposition, though for different reasons, as did three states with perhaps the longest traditions of maritime archaeology – Greece, Turkey, and the UK. Indeed, it is difficult to consider these early years of the Convention as a success in terms of building a durable consensus regarding UCH.

Despite these tensions as well as the Convention’s ambiguity and complexity, it does commit parties to some fundamental principles – a preference for in situ preservation “for the benefit of humanity” (Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, 2001, p.3), the eschewing of commercial exploitation, and a commitment to public access, among others. Furthermore, although the Convention affirms sovereignty and custodial responsibilities of coastal states in managing sites within their territorial waters and up to their continental shelf area, it also encourages the involvement of flag carriers and states with a “verifiable…cultural, historical, or archaeological link” to wreck sites, affording them rights depending on the specific location (i.e. in territorial or contiguous zones, exclusive economic zone, or continental shelf) of the wreck, state craft designation, etc. As the Convention makes no provision for a judicial or enforcement body to drive implementation or settle disputes, it requires and in fact demands multilateralism to become the de facto regime governing underwater cultural heritage.

At first glance, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) and greater Mediterranean region is among the most challenging places for the Convention’s impact to materialize. The legacy of a long and troubled past – colonialism, border disputes, and war – exhibit several tensions discussed above: colonial powers vs. their colonies, flag vs. coastal states, and several active territorial conflicts. And yet, recent years have seen progress. A prime example of this has been the Skerki Bank and the Sicilian Channel Mission.

Covering an area some two hundred nautical miles in length bounded by Tunisia to the southwest and Sicily in the northeast, this stretch of water/sea has served as a natural bottleneck for shipping from antiquity through today. Scene of trading routes between ancient Rome and Carthage as well as the Medieval Fatimid state in Sicily with its North African base, fierce action in both World Wars, and some of the busiest flows of migrants in the 21st century, the area has been a hotspot for maritime activity for as long as people have taken to the seas. A range of shallows, reefs, and other geological features have made it a veritable graveyard for ships throughout the ages, with hundreds of wrecks suspected. This presumed wealth of archaeology encouraged unchecked looting of the sites as recreational diving took off in the 1960’s. Suspicion, hearsay, and findings from isolated archaeological projects gave a fragmented picture as to what lay on the seabed until a more holistic and extensive study of the area was conducted by Robert Ballard and Anna Marguerite McCann during four separate expeditions from 1988 to 1997. Their work detailed eight wrecks spanning over two thousand years of nautical history and confirmed the Rome-Carthage trade route.

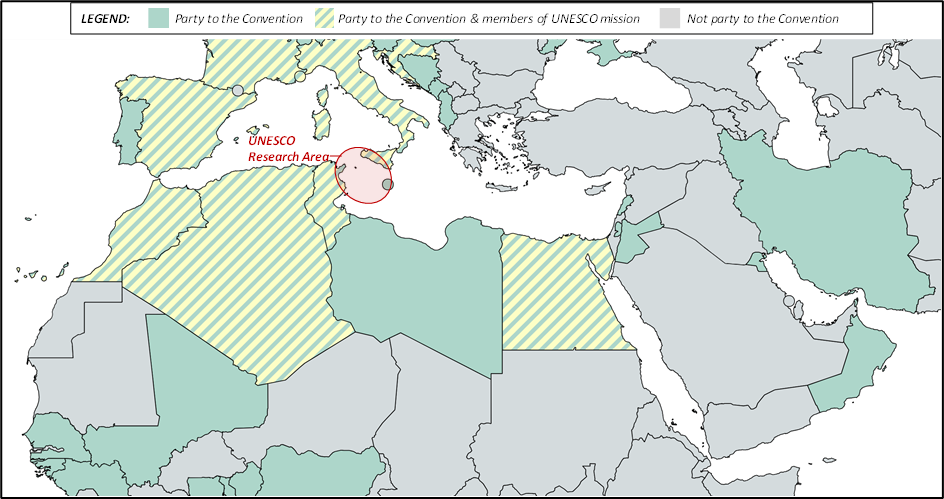

Little had been done to study or protect the site until 2019, when eight countries, all party to the Convention, came together under the auspices of UNESCO to form that organization’s “largest and most ambitious international mission ever conducted” (UNESCO, p.1) to protect underwater cultural heritage (fig. 3). The team was comprised of archaeologists from Algeria, Croatia, Egypt, France, Italy, Morocco, Spain and Tunisia – a group representing former colonies and colonizers, current and former maritime powers from multiple historic eras, and countries with ongoing territorial disputes. The project took place over two weeks in 2022 and involved two robots – Hilarion and Arthur – which took some 400 hours of video over 20,000 images. Among their accomplishments were the complete mapping of a 10 sq km area of seabed, photogrammetric models of three Roman wrecks first noted by Ballard and McCann, and the identification of three new wrecks, one Roman and two late 19th/early 20th century. At the same time, as of 2023, a new project is underway to chart the seabed in this area using different geophysical techniques.

Despite these ‘green shoots’ of multilateral coordination to study and protect UCH sites in this area of the Mediterranean, one should not be naïve about the motivations behind such initiatives. UNESCO, among many other multilateral institutions, has often served as tool for neocolonialism and cynical realpolitik, producing decisions at times that are antithetical to its mission of protecting cultural heritage (Meskell, 2014). In recent years, it has become a battleground between traditional Western powers and the BRICS nations, with both camps politicking to win support of smaller countries in the developing world. MENA is of course one field of play in this game.

Though some can be sceptical as to whether the interest and benefits of this collaboration accrue equally to the participants, the Skerki Bank project presents a significant step in the right direction – a rare multilateral effort to document and protect shared heritage in international waters. The Western Mediterranean stands alone as a region in which coastal states are party to the Convention, raising the prospect for further collaboration of this kind. In this respect, the Skerki Bank serves as a model of multilateral cooperation to protect UCH and foster the Convention as a mechanism in the region and beyond. At the same time, it is important to acknowledge the humanitarian crisis unfolding in the same region and reflect on recent research at the intersection of heritage and the politics of migration and displacement (Hamilakis, 2017).

References

Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage (2001), UNESCO. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000126065.

Dromgoole, S. (2013). Underwater Cultural Heritage and International Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Hamilakis, Y. (2017). ‘Archaeologies of Forced and Undocumented Migration, Journal of Contemporary Archaeology, 3(2), pp. 191-294.

Hamilakis, Y. (2017) ‘Archaeologies of Forced and Undocumented Migration’, Journal of Contemporary Archaeology, 3(2), pp. 121-139.

Meskell, L. (2014). ‘States of conservation: protection, politics, and pacting within UNESCO’s world heritage committee’, Anthropological Quarterly, 87(1), pp.217-243.

UNESCO (2022). Multilateral Underwater Archaeological Mission under the Framework of UNESCO in the Skerki Bank and the Sicilian Channel. Available at: https://www.unesco.org/en/skerki-bank-mission.