Mark Goldstone

1855: the Crimean War rages, Britain and France collaborate, propping up a fading Ottoman Empire to defeat Russia. In Mesopotamia there has been an archaeological outbreak of cooperation. Old European rivals are surprisingly collegiate in their quest to find and excavate the ancient sites of Assyria and Babylon (Larsen 1994).

The 19th century was a formative period for Mesopotamian archaeology and big names such as Sir Austin Henry Layard, Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson and Paul-Émile Botta make even bigger “discoveries” at Khorsabad / Dur Sharrukin and Nineveh. However, the challenge of finding these sites was more than matched by the logistical conundrum of removing the objects to the museums of Europe (Larsen 1994). Given the extent of the loss it is surprising how few archaeologists know the story of the “Al Qurnah Disaster” in which a large consignment of antiquities sunk to the bottom of the Tigris in 1855 (fig.1).

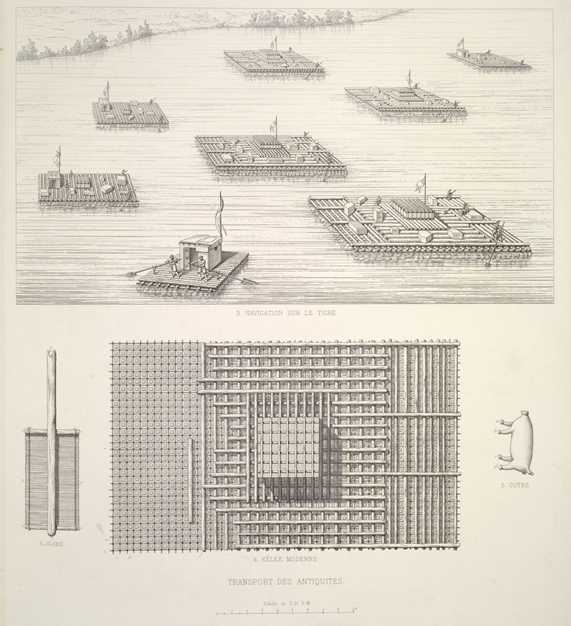

The original shipment from Khorsabad was loaded onto eight specially constructed rafts (keleks) and transported to Baghdad (fig.2). In charge, was Victor Place, who replaced Botta both as French Consul at Mosul and in leading the excavations. There was of course no profession of archaeology at this time and a political or military position often allowed for an extended trip to relevant sites. For example, Layard was employed in a series of minor political roles by the British Ambassador in Constantinople who encouraged his efforts to locate and recover antiquities (Larsen 1994).

Having successfully reached the capital, Place was called away, leaving A. Clement, in charge. The four larger rafts with colossi were retained but the contents of the smaller ones were packed onto a 50-ton ship for onward transport. Additional antiquities from other excavations were also loaded on board. Though some inventories do exist they are far from comprehensive. Julian Reade (2018) has compared what survives in museums with original excavation reports and drawings to provide the most detailed account on which the following list is based:

- 41 cases of wall reliefs, sculpture, and glazed bricks from Khorsabad city gate 3 (fig.3), The Sin Temple and Northwest Palace (Place / Clement’s Consignment).

- 31 panels from the North Palace at Nineveh (from Layard).

- 80 cases of mixed antiquities, some from Nimrud, bound for the Berlin Museum (from Layard).

- 41 cases from Fresnel’s excavation at Babylon including 80 cylinder seals, amulets, terracotta figurines, glazed brickwork and 14 cuneiform tablets both stone and clay. Some of the brickwork may be from the Ishtar Gate.

Nineteenth century archaeologists were under pressure to recover artifacts for the museums of Europe thus generating enough interest (and money) to allow their work to continue (Larsen 1994). The plan was to continue down river to Basra and meet a waiting ocean-going ship for onward transport to Europe. Ships will not wait forever, and it was this pressure that likely compelled the party forwards despite repeated warnings regarding the instability and banditry present on the route south (Egami 1972, Genç 2021). Advice against further transportation from Baghdad is also recorded in official Ottoman archives (Genç 2021).

The Ottoman empire was in significant decline with many former territories having already gained independence, and with war presenting an existential threat the authorities’ focus was firmly on the Crimea. Between the main cities of Iraq, tribal regions are described as somewhat anarchic, potentially in revolt and highly dangerous (Baer 2021).

The foreboding of the Ottoman officials proves accurate. Shortly after passing the Tomb of Ezra, a mausoleum sacred to both Muslims and Jews, the ship was repeatedly attacked by canoe bound assailants, perhaps members of the Beniram and Mousabet tribes (Egami 1972), but about whom we can find out little. We presume they are family sub-sections of the larger Muntafiq tribe who remain in the region to this day.

Though Clement was prepared to engage in gift exchange for safe passage through tribal areas (Larsen 1994), he was forced to give the entirety of these gifts to the first Sheikh he encountered upstream. As a result, nothing remained for later tribes who felt they had a legitimate reason to take possession of what was available, particularly the regionally rare and valuable commodity of wood stripped from the rafts (Larsen 1994).

The original report of Place tells us that eventually the ship ran aground on the “left” (presumed eastern) bank, the four rafts however were able to continue past Qurnah at the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates. Two rafts made it to Basra, one was grounded and later recovered and the last sunk to the bottom of the Shatt Al Arab (Egami 1972), as the post confluence river is known.

River transportation logistics

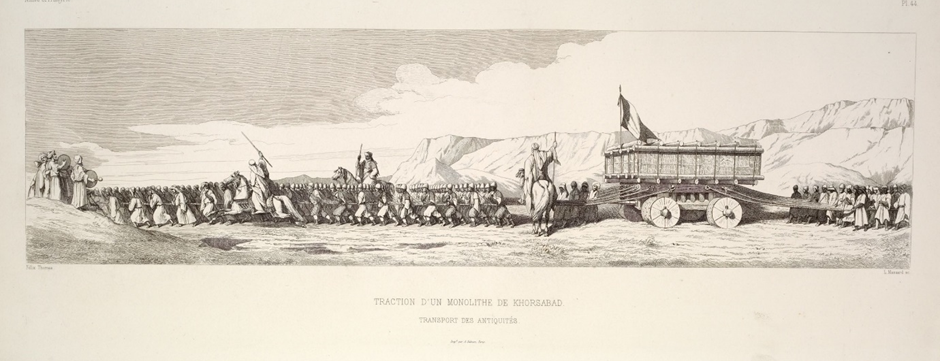

Though the industrial revolution was well underway in Europe by 1855, in this part of Iraq only rope, wood and human determination were available to transport large cargo (fig.4).

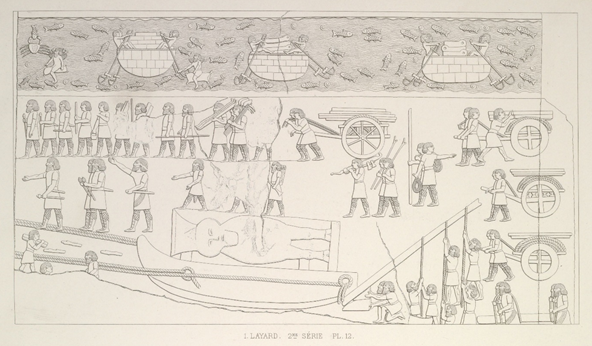

The sinking of the rafts is reminiscent of Sargon’s attempts to transport colossal figures to Khorsabad in the 8th century BCE (fig.5):

Assur-sumu-kein called me to help and loaded the bull colossi onto the boats, but the boats could not carry the load and sank.

Parpola 1987: 94

Sennacherib had similar issues with colossal figures intended for the old palace at Nineveh sinking in the river (Reade 2018). The issue of weight was just as prescient in the 19th century sometimes leading to artifacts being cut into pieces for transport (Reade 2018).

Search Not Rescue

Having had both his clothes and shoes stolen in the attack, Clement seriously injured his feet whilst looking for assistance and was only able to walk again after some ten days of recuperation in Basra. Daniel Potts (2020) has recently provided a translation of Clement’s account in English and found no reason to doubt its veracity. It is a sombre account that does not try and portray the author in a heroic light. Further, we know Clement was taken in by the English Consul at Basra to whom his injuries would have been obvious.

Having convalesced, Clement made two attempts in June 1855 to recover the cargo of the rafts. Though he was able to locate the ship with relative ease, he was unable to salvage its contents. According to Clement’s description (summarised by Egami 1972: 9) “They located the ship lying at right angles headed toward the bank, with the left gunwale severely tilted toward the stern. The ship’s bow stuck about twenty-five centimetres above the water but the stern was thrust one meter into the mud bottom under three fathoms of water”.

No further attempts at location and recovery were made until 1971 by a Japanese team led by Namio Egami (fig.6). The team was able to conduct useful surveying work and use the primary sources in French to identify the most likely site of the wreck, predicting possible shifts in the river course. However, their remote sensing equipment, the “sonostrator” (early sonar equipment) – failed and was not able to verify the location of the wreck (Egami 1972).

Accounts of the unrecovered raft were less reliable – there were some reports of local witnesses seeing the fated raft sink some 16km north of Basra. With such a vague location it is difficult to narrow to a tight search area (fig.7).

State of Preservation

Despite numerous descriptions of the cargo limited emphasis has been placed on its state of preservation. Though it is possible that the ship may now be buried in the banks of the Tigris, we must allow for at least a good deal of water damage in the last 168 years. A 50-ton boat laden with heavy stone objects, carefully packed in wooden crates, is unlikely to have shifted position in the relatively benign waters of the lower Tigris so, like Egami, we presume it to be in place. Soaked wood can of course eventually disintegrate, however it is likely that this time period is not long enough for complete destruction, and it may well have been preserved in sediment.

It is not good news for the wall reliefs made from gypsum and limestone, which are soft and highly soluble. A case in point is a human headed winged bull made of gypsum exposed when the riverbank disintegrated at Mosul near Khorsabad in the 1930s. Lost by the original sculptors, 2,500 years of water damage have severely eroded the artwork (Reade 2018). However, the reliefs lost at Qurnah have only seen a fraction of this exposure.

In preparation of this article, I asked several archaeologists about the state of preservation with little consensus, with multiple unpredictable factors impeding a definitive conclusion. What we can say is that some of the objects are likely to have fared better than others.

In this context, the Mohs Hardness Scale is predictive of materials’ solubility in water.

Table of Materials On Board with Mohs Hardness Rating

| Material | Items | Mohs Hardness Rating |

|---|---|---|

| Alabaster | Reliefs/Sculpture | 1.5 |

| Gypsum | Reliefs | 2 |

| Limestone | Reliefs | 3-4 |

| Haematite | Mace heads | 5 |

| Calcedony/ Quartz | Amulets / Seals | 7 |

| Glazed Brick | Wall panels | 6 |

| Jasper | Amulets | 5-7 |

According to the table above, reliefs of gypsum are likely to have suffered the worst damage. Tablets and other objects made from clay are likely well preserved if they are fired. A much poorer outcome is predicted for merely sun-baked clay. It is likely that the fired glazed brick works are largely unharmed the potential pieces of the Ishtar Gate being particularly tantalising.

Cylinder seals and amulets can be made from a wide variety of materials. Clay, ivory, glass and a variety of metals are all common and would variably suffer water damage accordingly.

Approaching Al Qurnah in 2023

Archaeological techniques have moved on significantly since 1971. Any team searching for the wreck would now have a plethora of satellite detecting technologies, LIDAR and GPR alongside modern sonar and deep-water surveying techniques.

Despite the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office still advising against all travel, archaeologists from the UK alongside a host of other nations have returned to Iraq to pursue research. The region is still rebuilding after the upheavals of recent decades and there is already an excess of archaeological material awaiting more detailed processing and assessment. There is also the key issue of preserving as much as can be salvaged from sites affected by ISIS. It is in this context that any modern attempt at location and recovery would need to take place, a question then of priorities.

Part of the attraction of this story are the multiple juxtaposed socio-political and technological contexts in which it unfolds across disparate slices of time. The Assyrians and 19th century explorers shared the challenge of moving large statues on the river and as we have seen both failed on occasion. Political instability in the form of a waning Ottoman Empire and tribal revolt combines with political pressure to recover artifacts to Europe. The result, poor decision making and predictable disaster. The situation is not helped by the 19th century methodologies and limited use of meticulous inventories meaning, despite the best efforts of modern scholars, even being categorical about what has been lost is impossible.

Technology and more specifically the failure of the sonar equipment halts the expedition of 1971 and any attempt to deploy the most modern archaeological methods would have to take place in an Iraq still in the midst of post-conflict reconstruction. Given all the above it would be good to at least identify the site of the unfortunate ship so laden with debatably decaying artifacts in order that it can be protected and studied further.

Cited References

Baer, M. (2021) The Ottomans. Khans Caesars and Caliphs. Hachette: Basic Books.

Egami, N. (1972) The report of the Japan mission for the survey of the under-water antiquities at Qurna. The first season (1971-1972_). Bulletin of the Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan_ 8: 1-36.

General Research Division, The New York Public Library. “Transport de matériaux. Motifs extraits des bas-reliefs.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1867. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e2-f699-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Genç, B. (2021) Memory of destroyed Khorsabad, Victor Place, and the story of a shipwreck. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 31(4): 759-774

Larsen, M.L. (1994) The Conquest of Assyria. Abingdon: Routledge.

Parpola, S. (1987) The Correspondence of Sargon II. Part 1: Letters from Assyria and the West. SAA 1. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press.

Place, V. (1867) Ninive et l’Assyrie. Paris: Ministère de la Maison de l’Empereur et des Beaux-Arts.

Potts (2020) ‘Un coup terrible de la fortune:’ A. Clément and the Qurna disaster of 1855. I n Finkel, I.L. and Simpson, St J., eds. In Context: The Reade Festschrift. Oxford: Archaeopress: 235-244.

Reade, J. (2018) Lost in Translation. Journal of Cuneiform Studies. Vol. 70: 167-188.

I love this,. So exciting,It’s amazing 😍😍