by Athena Trakadas and Azzedine Karra

Introduction

Essaouira is a picturesque city located on the Atlantic coast of Morocco, ca. 650 km south of the Strait of Gibraltar (Figure 1). The walled historical settlement lies on low sandstone outcrops that form the northern promontory of a semi-circular bay lined by a wide sand beach. Several hundred metres offshore to the south-west are low islands that are a protected nature reserve for migrating birds. Across from the islands the Oued (river) Ksob (designated a RAMSAR site in 2005) empties into the bay after cutting through scrubland and sand dunes.

Essaouira was inscribed in 2001 to the UNESCO World Heritage Site list due to its “late 18th-century fortified town, built according to the principles of contemporary European military architecture in a North African context” (UNESCO n.d.). Today, it is a well-known tourist destination, and shops in its walled medina sell textiles, pottery and art; offshore, swells from the Atlantic break between the rocky promontories of the mainland and islands to create ideal conditions for the kite- and wind surfers. Morocco’s recent focus on development and tourism in the region has resulted in an expanded fishing port, and an increasing number of restaurants, hotel and golf complexes lining the bay’s corniche and extending into the once-open dunes behind the city.

A brief history

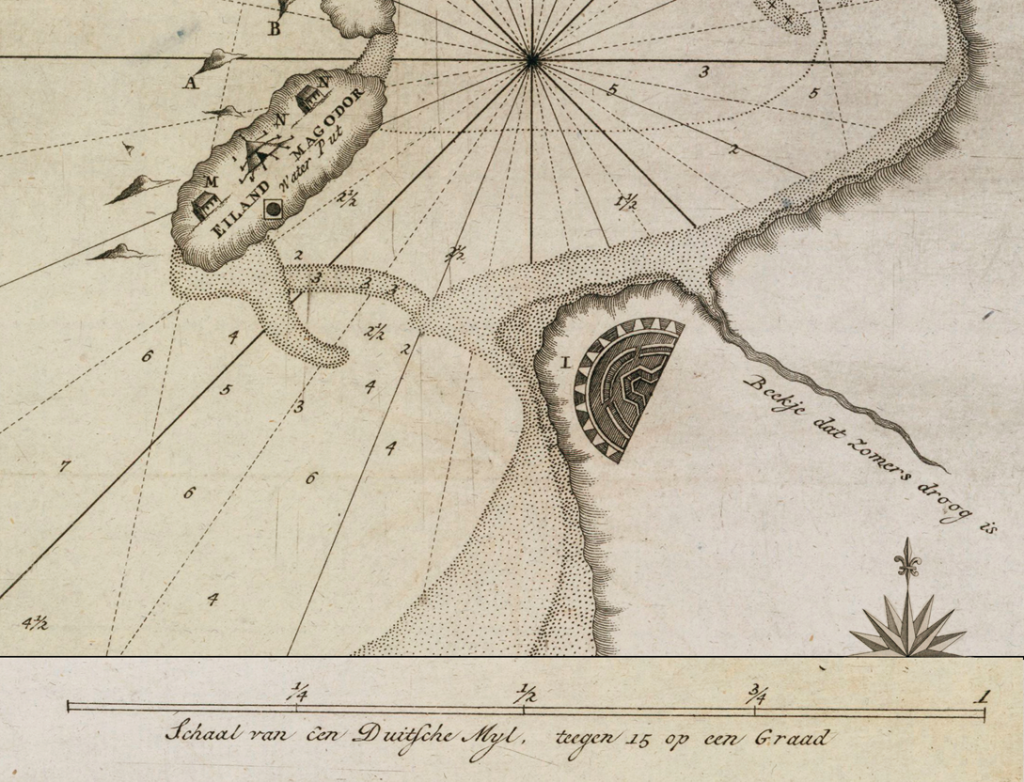

Historically called Mogador, Essaouira has for millennia served as a safe harbour for trade ships seeking access to goods from the hinterlands up and down the northwest African coastline (Figure 2). The islands, referred to collectively as ‘Îles Purpuraires’, bear archaeological traces of the earliest contacts. The northern, second-largest island (Île du Pharaon or Dzirt Faraoun) has evidence of prehistoric occupation as well as some Phoenician material dating to the 7th century BC. On the southern and largest island, called Essaouira Island or Mogador Island, are the remains of a Phoenician trading and manufacturing site, dating to the 7th-6th centuries BC. Subsequent occupation layers include Punico-Mauretanian pottery and a Roman villa, dating from the 5th century BC to 4th century AD.

The islands are often identified as the ancient Insulae Purpurariae of the Mauretanian king Juba II, who, Pliny notes “established there the manufacture of Gætulian purple dye” from murex/purpura sea shells in the 1st centuries BC/AD (Pliny, Natural History 6.36.202, 6.37.203). These islands are sometimes associated by scholars with ancient Cerne, from Hanno’s Periplus (§8-11) (although Pliny keeps these two separate, Natural History 6.36.199).

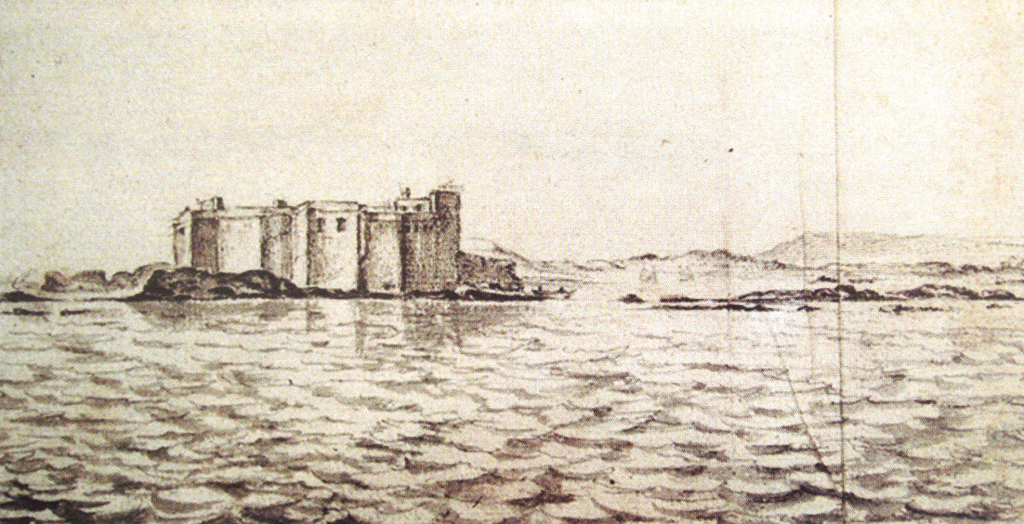

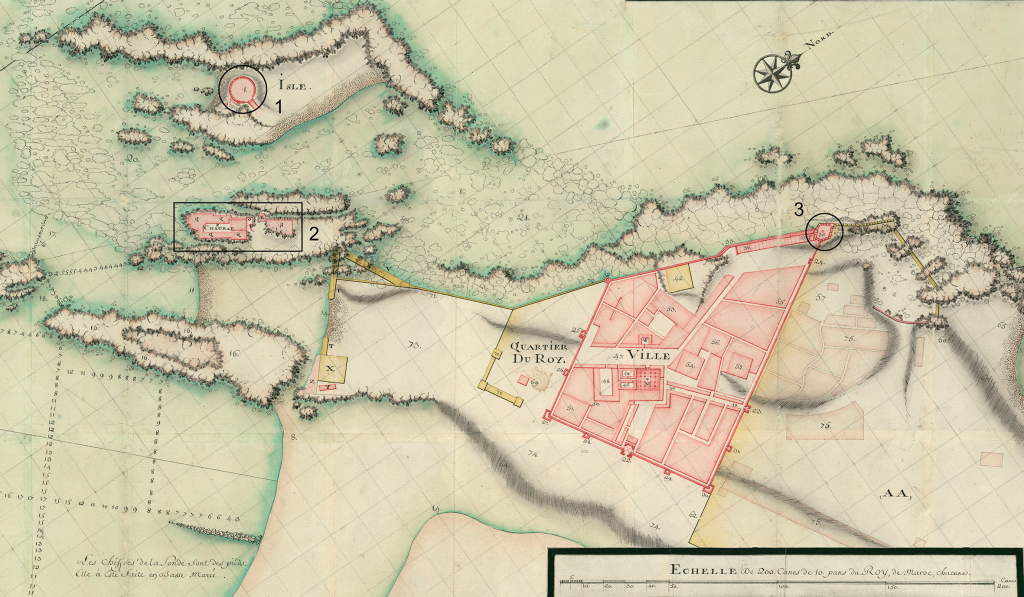

The establishment of Essaouira on the mainland, adjacent to a protected anchorage, is directly connected to the historical European powers’ struggle for control of West African trade. In the Portuguese navigator Duarte Pacheco Pereira’s early 16th-century guide, Esmeraldo De Situ Orbis, he notes that “ships of 100 tonnes … can moor with an anchor and a cable behind the island in depths of 6 or 7 brasses” (Ricard 1927: 249). In 1506, the Portuguese built a fortification, Castelo Real, on the promontory that forms the western edge of the modern port to protect the entrance to the natural anchorage (Figure 3). Castelo Real served as part of the chain of Portuguese coastal stations along the Moroccan coast between Larache to the north and Santa Cruz (Agadir) to the south but was abandoned in 1510 or 1512 due to the successful armed opposition of local Berber tribes.

Expeditions of the English in 1577 and French in 1629 attempted to occupy Castelo Real to force trade concessions; repelled by local Moroccan forces, nothing permanent was ever established. In the mid-18th century, however, the Alaouite-dynasty Sultan Moulay Abdallah and his son Mohammed Ben Abdellah al-Khatib signed numerous trade and peace treaties with European powers, curtailing local piracy and opening up sea lanes. Mohammed Ben Abdellah, based inland at Marrakech, decided to develop Essaouira as the main trade port for the trans-Saharan routes instead of the previously favoured Agadir, to the south, and Safi, to the north. Beginning in the mid-1760s, European and Moroccan architects and builders, including Théodore Cornut from France, laid out the fortified city of Essaouira (Figure 4).

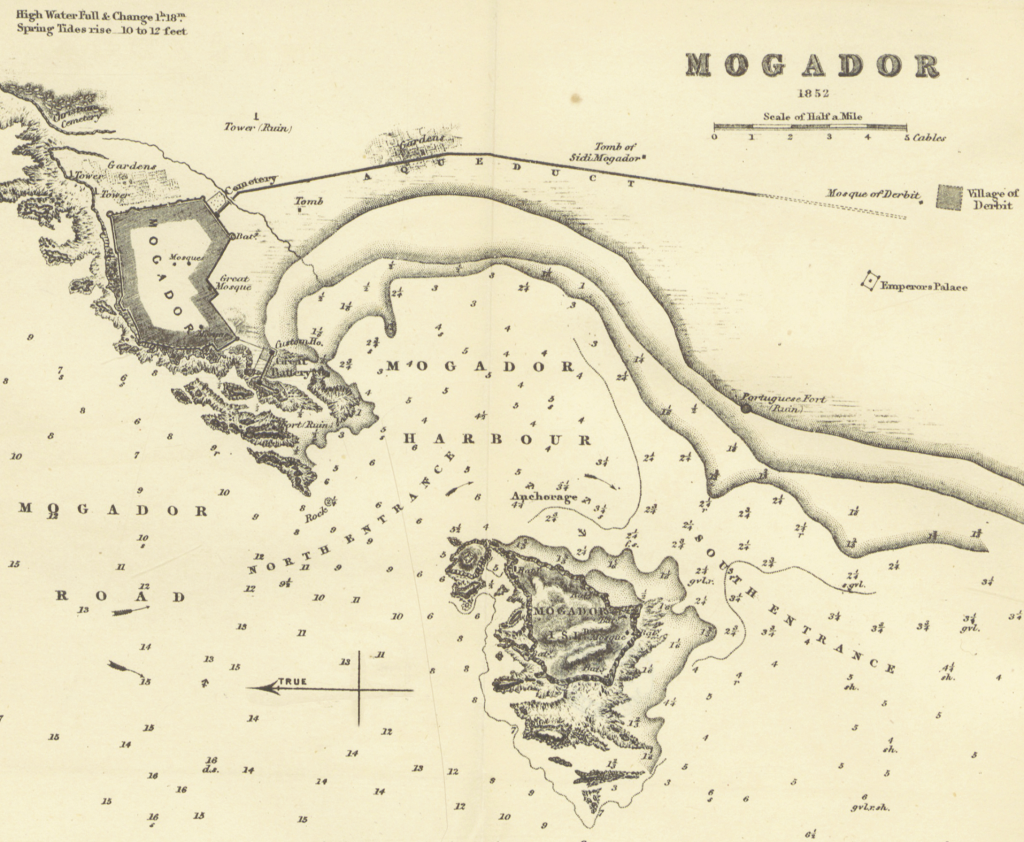

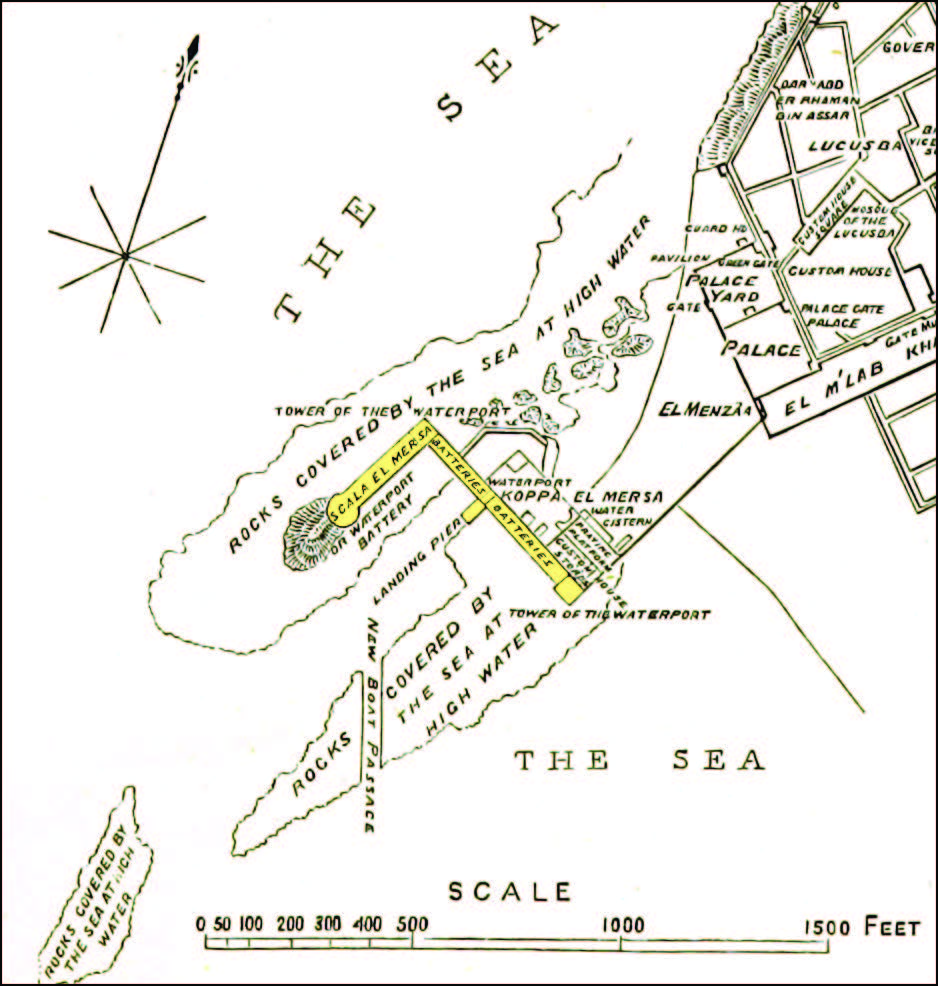

Placed slightly north of and behind the remains of Castelo Real, the new settlement had unusually wide streets, and districts for the royal household, European and Moroccan traders (with a large population of Jewish Moroccans), and foreign diplomatic missions. Facing the Atlantic, the walls of the city are still guarded by canon-lined ramparts, with circular crenelated towers. The main tower of Sqala (or Skala) del la Kasbah juts out on top of rocks over the sea and the East Bastion faces in the direction of the Marrakech road. Eventually a tower, Sqala (or Skala) de la Marine, was built over the remains of Castelo Real to guard the western entrance to the port. An additional circular tower (called “fort ruin”, “lighthouse” or “old tower” on maps) located on a small rock outcrop a few hundred metres to the west further protected the entrance to the port (Figures 5 & 6).

Figure 5. View from Sqala de la Marine north along the city ramparts to the point of Sqala del la Kasbah. Taken in 2019 (A. Trakadas).

Figure 6. View from Sqala del la Kasbah south along the city ramparts to (1) Sqala de la Marine, (2) ‘Îles Purpuraires’, (3) the circular tower/”ruin”. Taken in 2003 (A. Trakadas).

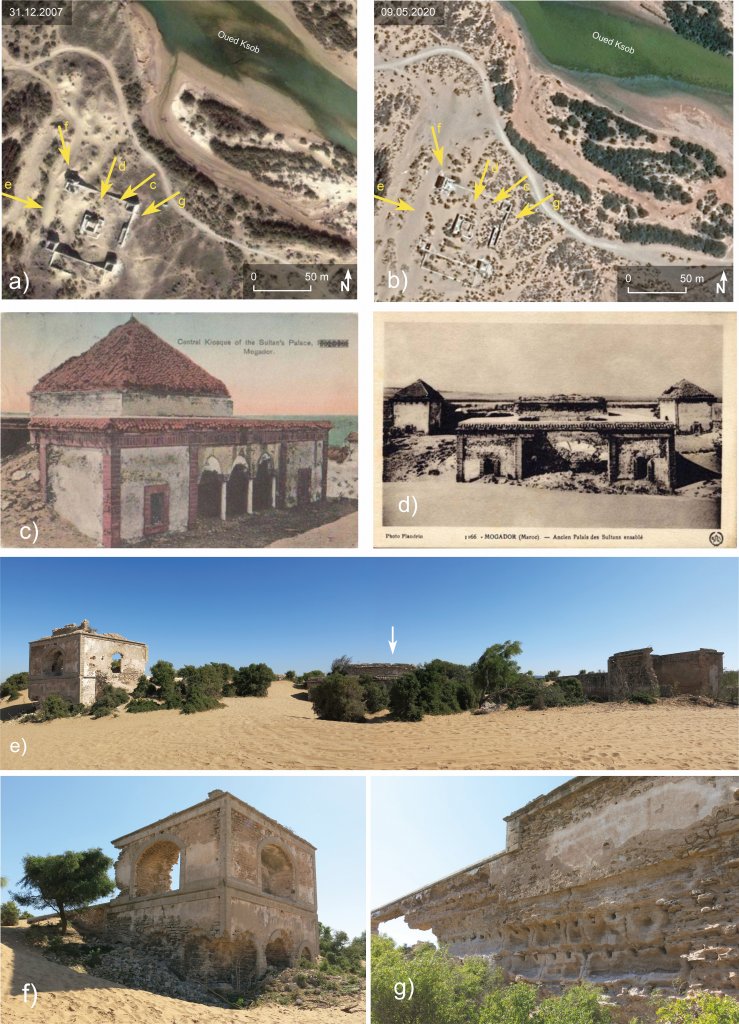

Structures ex-muros include an aqueduct, which first appears on a city plan in 1840. Later maps show its route to the south from the walled city’s Bab Marrakech, passing in front of the marabout (shrine) of Sidi Mogador (or Sidi Mogdoul) to the Oued Ksob in front of the village of Diabat/Diabet (or Derbit). Near the river, between the aqueduct and the beach, a palace called Dar Soltane (or Dar al-Baïda) was built for Mohammed Ben Abdellah, designed by the Moroccan architect Houbane (Figure 7). On Cornut’s map of 1767, a rectangular structure faces the sea near the river mouth, noted as a “battery made of wood, at the height of the dunes” with cannons. This structure is absent on later maps, but a circular or semi-circular structure, the Borj el-Baroud, appears on maps after 1790 (see Figure 9 below). At least five semi-circular batteries were constructed on Essaouira Island to guard the entrances to the bay and port and appear as “projected batteries” on Cornut’s 1767 map: Borj el-Âssa is the largest of these, and with its adjacent mosque, faces east, guarding the southern entrance to the bay along with Borj el-Baroud opposite (Figure 8). A large high-walled rectangular enclosure on the island appears on maps in early 1900s, serving at the time as a prison and quarantine station (see Figure 2).

Archaeological investigations

The eastern coast of Essaouira Island has been the primary focus of archaeological investigations in the region (see Figure 1, #8). The first phase of excavations took place under French-Moroccan direction between 1951 and 1960 and identified “pre-Roman” and Roman layers. A small-scale excavation was conducted at the site in 2000 by researchers from Institut National des Sciences de l’Archéologie et du Patrimoine (INSAP) and Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Between 2006 and 2008, an INSAP and Deutsche Archäologische Institut-Madrid (DAI) team reinitiated excavations. The combined findings from these campaigns reveal a Phoenician presence in the mid-7th-6th centuries BC on the southeastern edge of the island. Findings include a possible shrine to Astarte, along with slag, bellows, and iron rods, indicating iron working. It has been suggested that erosion along the island cliff face has removed a large portion of the archaeological material dating to this earliest identified habitation phase.

There is a limited amount of material present on the island dating to the following centuries (the Punico-Mauretanian period), although pottery from both the western and eastern Mediterranean are present. A more permanent presence is traceable in the early 2nd century AD, during the Roman period. This material is distributed throughout the island, with the main concentration on its eastern side, adjacent to and north of the earlier Phoenician site. Here, a ca. 2,200 m2 building identified as a villa with mosaic floor, peristyle courtyard and cistern, has been partially excavated. At the southern edge of the Roman villa site are two rock-cut fish-salting vats (cetariae). The site was inhabited until the end of the 4th century AD and a nearby necropolis dates from this latter part of this period. Recently, fishermen have recovered several complete amphorae from the waters around the island – dating from the 1st to the 3rd-4th centuries AD – and originating from the Aegean and southern Iberian Peninsula.

Elephant, peacock, lion and fish bones, bronze fishhooks, and shellfish have been found in occupation layers on the island. Trade in exotic animals might have existed, and certainly the local marine resources were exploited. Pliny’s text suggests that purple dye manufacturing was undertaken on the islands in antiquity. However, there are yet to be found traces of the dyeing process: large deposits of murex/purpura shells, which are broken or appear to have been affected by firing.

Examples from the MarEA study

Overall shoreline change:

A. Jodin, one of the archaeologists who excavated Essaouira Island in the 1950s, originally proposed that in addition to the island, the rock outcrop upon which the historical walled city of Essaouira lies was also an island during the Phoenician to Roman periods, perhaps possessing contemporary sites. During the INSAP-DAI project, sediment cores were taken throughout the region to clarify the development of the coastline. The results of this research established that ca. 3,000 BC, modern-day Essaouira Island and Essaouira were islands, with the mainland coastline lying 500 m to 1 km inland of its present location (see Figure 1). Sediment accretion began to occur after this, affecting the morphology of both islands. By ca. 700 BC, Essaouira Island, slightly larger than it is at present, was connected to the mainland by a wide tombolo, with the mouth of the Oued Ksob 1 km to the south of this. The former island under modern Essaouira became part of a long peninsula, connected to the mainland at its northern end with a long lagoon to the east. The coastline lay 1 km west of its present location.

In the last two millennia, the lagoon infilling continued, and the tombolo to Essaouira Island diminished. Historical maps from the 1736, 1761, 1764, and the 1790s show a shoal or sandbar present where the tombolo had once been (Figure 9). It is missing from an 1884 map, but the southern passage into the bay was noted “… to be filling up” (Imray & Jenkins 1884: 513). In the late 20th century, local residents recount seeing a sandbar sometimes exposed between the island and mainland at low tide.

During the last few

centuries, the location of the mouth of the Oued Ksob has fluctuated repeatedly

(see Figure 1, #6). Maps

dated to the 1790s and 1893 locate the battery of Borj el-Baroud on the

coastline and to the south of the mouth of Oued Ksob (see Figures 7 & 9). Maps from 1884, 1896

and 1917 locate Borj el-Baroud slightly more inshore than it is at present, and

to the north of the Oued Ksob mouth. Likewise, Dar Soltane, presently south of

the Oued Ksob riverbed, was located to the north of the river in 1884 and 1896 maps

but south of it in 1893 and 1917 maps (see Figure 1, #5). The course of the lower riverbed cuts through

active dunes and is impacted by sand deposited from aeolian re-shaping of these

from the north. During winter rains, upstream sediments combined with sand empty

into the bay, which are then carried north by near-shore currents and re-deposited

on the beach to the south-east of Essaouira. The process also causes the water

in the bay to turn muddy-brown during high-impact floods. In 2008, the

Moroccan government begun building a dam, Barrage Zerrar, 30 km upriver. This and

cement canalization of the present riverbed a few hundred metres inshore has

begun to severely regulate fluvial sediment deposition downstream, although aeolian-driven

sand dunes are actively covering more stable structures like Dar Soltane.

Archaeological features/Historical buildings:

The dynamic environment described above, where the two historical structures near the Oued Ksob are located, is clearly impacting the integrity of these sites. Dar Soltane is not only being covered by active sand transport but has undergone extensive weathering. As with many coastal structures, salt corrosion and water and wind erosion have degraded its plaster and sandstone. The structural integrity of Dar Soltane has considerably weakened since the beginning of the 20th century, with the collapse of walls and roof elements (Figure 10).

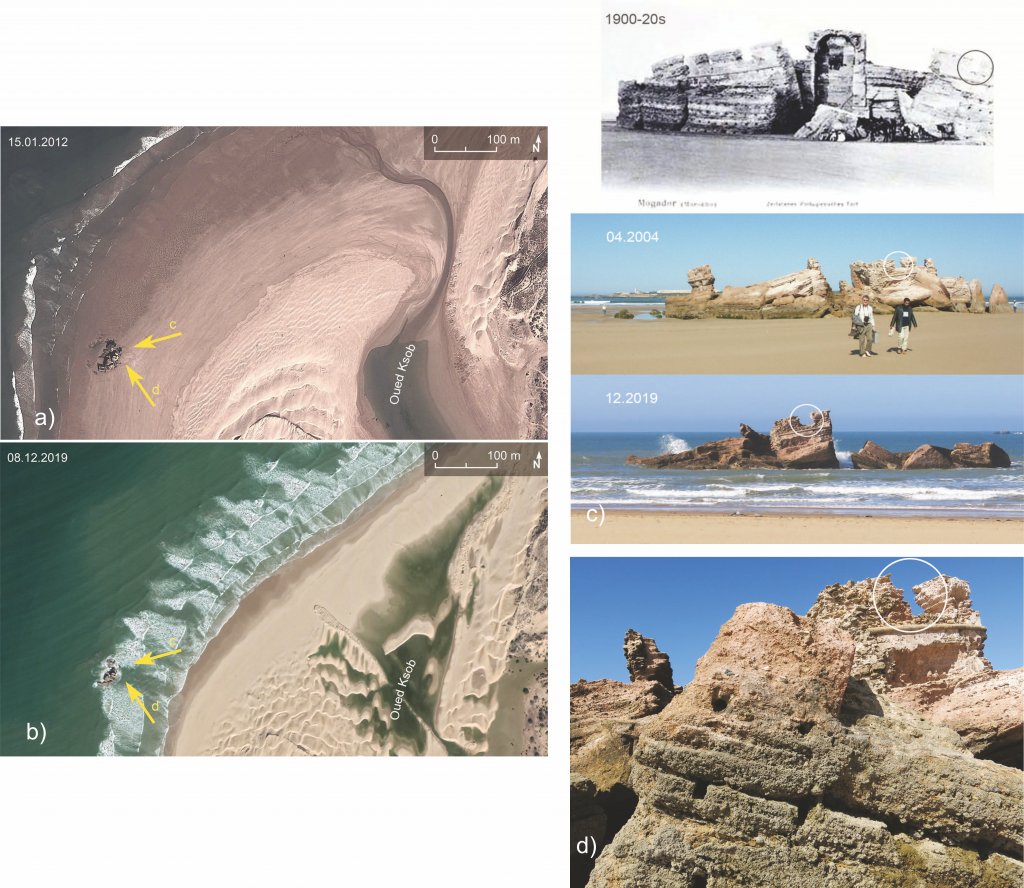

Borj el-Baroud has not only been occasionally exposed to flooding from the river on its eastern side, but daily inundation from the seaside. During high tides, the foundation of the battery is covered by water; during low tides it is fully exposed with the western edge lapped by waves (Figure 11). Wave action and daily tidal cycles (changes of ca. 2.5 to 3 m) have eroded the sandstone and mortar construction of the battery. Borj el-Baroud might have been originally built in the tidal zone (possibly on a small rock outcrop) in the late 18th century, but sea level rise (SLR) has contributed (and will continue to contribute) to its destabilization. Already in 1852, a map notes the structure as “ruins”, as do subsequent maps (see Figure 7). SLR, coupled with erosion from wave action and tides, and liquefaction of sediments, will continue to be a problem at this site.

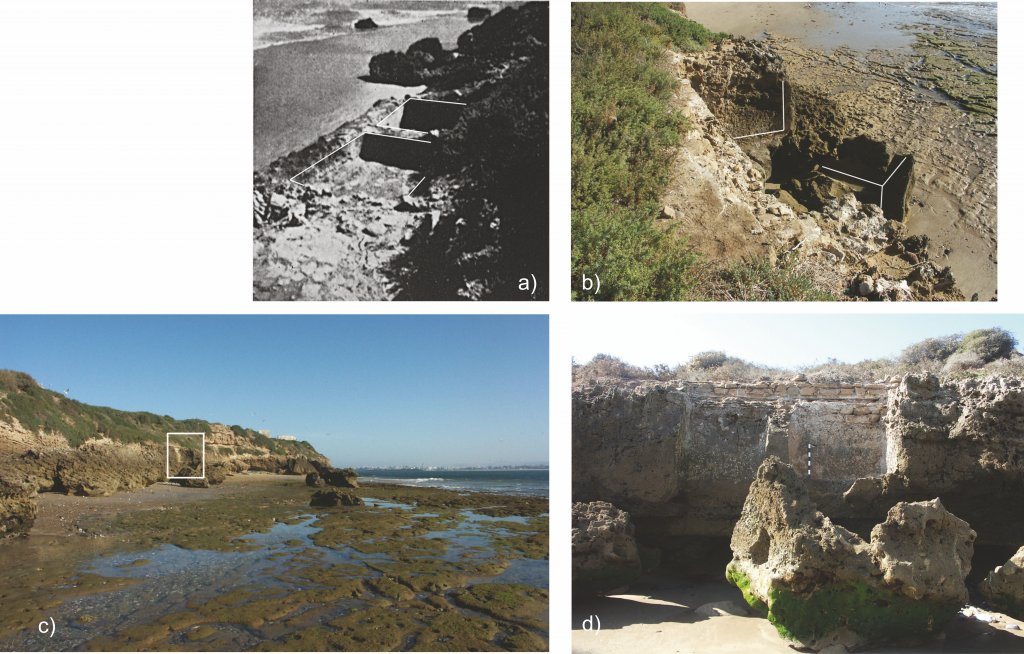

Also impacted are the two Roman water-proof salting vats (cetariae), located on the cliff face on the eastern coast of Essaouira Island, cut into the island’s sandstone and sealed with opus signinum and stonework around the upper edges. These were still intact in 1955, but by the early 1960s, their sea-ward faces had broken off and now lie on the beach, affected by tides (Figure 12). No doubt SLR and general coastal erosion processes will further impact what remains of these vats.

Port infrastructure:

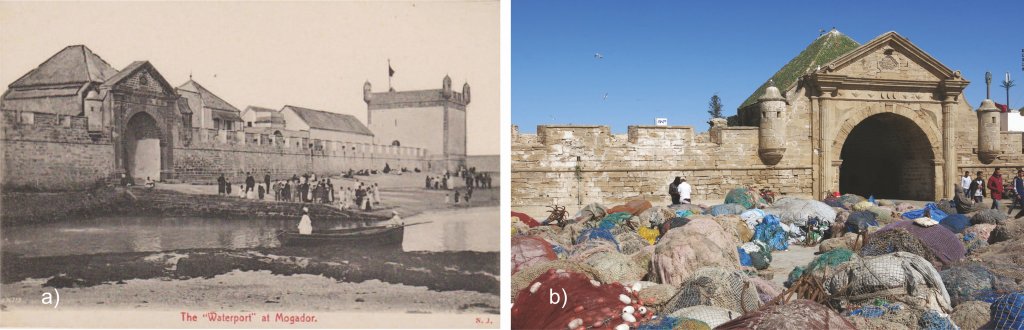

The waterfront at the northern end of the bay has undergone the most physical changes in the last few centuries. On the main rocky promontory here above the high tide line, Castelo Real was constructed in 1506 or shortly thereafter. Its general plan and walls were clear when Cornut began his grand design, and he notes it on his 1767 plan as “the ancient house [chateau] constructed by the Portuguese… and abandoned for 400 [sic] years” (see Figure 1, #1; Figure 3; Figure 4, #2). The chateau/Castelo Real was eventually incorporated into or razed to make room for the later port tower, the Sqala el Marsa (or Tour de la Marine) (see Figure 6, #1), and its rampart – not present in maps from the 1790s but visible in an 1852 map (see Figure 7). An L-shaped rampart connects the tower to the custom’s house, in which the sea gate, Bab el Bhar (or Porte de la Marine), opens onto a shoreline of sand and rock (Figure 13). A ramp led from the Bab el Bhar directly to the sea, comprising an area noted as “landing place/landing pier/waterport” on maps and in early 20th-century postcards (Figure 14).

In 1915, the ramp area and sloping shoreline in front of the Bab el Bhar were filled in to form a quay, and two jetties, both just under 300 m long, were built on top of rock outcrops. The new area covered 4 ha with additional structures for ship repair. Between 1924 and 1967, additional infilling took place and one of the jetties was extended to 373 m. In 2015, construction began again to expand the port by 2 ha, adding a boat crane, ice facilities, and parking lot to its southeastern section. These works were largely complete by late 2019 (Figure 15).

References:

ANP (National Ports Agency) n.d., Port of Essaouira (https://www.anp.org.ma/En/Services/Essaouiraport/Pages/Presentation.aspx, accessed 7/2020)

Brückner, H. & J. Lucas, “Landschaftswandel und Küstenveränderung im Gebiet von Mogador und Essaouira – Eine Studie zur Paläogeographie und Geoarchäologie in Marokko,” Madrider Mitteilungen 51 (2010): 99–108

Cornut, T., Plan de la Grande Isle de Mogador et de ses Environs, Remply des Ecueils, de la Rade, du chateau et de la nouvelle ville Suera en Barbarie, a trente Lieues du Maroc. Dedié a Monseigneur, le duc de Choiseul, Ministre de la guerre, et Secretaire d’Etat, pour donner a son Excellence, un connaissance parfeite de cette place, et de l’humeur de ses barbares (Paris 1767)

Desjacques, J., & P. Koeberlé, “Mogador et les Îles Purpuraires,” Hespéris 42 (1955): 193–202

Elmimouni, A., L. Daoudi & E.J. Anthony, “Morphological change on a wadi-influenced beach: Essaouira, Morocco,” Géomorphologie: relief, processus, environnement 20(3) (2014): 243–250

von Hellwald, F.H., Voyage dʹAdrien Matham au Maroc (1640-1641): journal de voyage publié pour la première fois avec notice biographique de l’auteur (La Haye 1866)

Imray, J.F. & H.D. Jenkins, Atlantic Ocean Pilot. The Seaman’s guide to the navigation of the Atlantic Ocean, with numerous illustrations, charts and plans (London 1884)

Jodin, A., Les etablissements du Roi Juba II aux Îles Purpuraires (Mogador) (Tangier 1967)

Van Kuelen, G.H., Verklaaring van deeze Paskaart sedy besorktom is de Graf plaats van een Marabouw, hebbende rondom de muer cenige spitze Naaden, Zynde een goed merk als men uit het Noorden komt om niet roorby Magodor te zeilent Rif Teran van de Mooren aldus genaamd, loopt meest W.Z. W. omtrent 5/8 Myl van de wal in zee, Omtrent a Mylen benoorden Magodor begint het Land zig hoogte vertonen met witte zandbergen, die tot ruim Myl bezuiden gemelde plaats voort Strekken (Amsterdam 1790s)

Leared, A., Morocco and the Moors: being an account of travels, with a general description of the country and its people (London 1876)

López Pardo, F., A. El Khayari, H. Hassini, M. Kbiri Alaoui, A. Mederos Martín, V. Peña Romo, J. Suárez Padilla, P.A. Carretero Poblete & B. Mlilou, “Prospección arqueológica de la Isla de Mogador y su territorio continental inmediato. Campaña de 2000,” Canarias Arqueológica 19 (2011): 109–147

Marzoli, D., & A. El Khayari, “Mogador (Essaouira), Marokko. Ein phönizischer Außenposten an der marokkanischen Atlantikküste. Die Arbeiten der Jahre bis 2018,” e–Forschungsberichte 1 (2018): 72–75

El-Mghari, M., “De Mogador à Essaouira: Genèse d’une ville Une ville ancienne est un corps vivant, modelé par une multitude de générations,” African and Mediterranean Journal of Architecture and Urbanism 2(1) (2020): 55–65

Ricard, R., “La côte atlantique du Maroc au début du XVIe siècle d’après des instructions nautiques portugaises,” Hespéris 7 (1927): 229–258

Rosser, W.H., North Atlantic Directory. The physical geography and meteorology of the North Atlantic; together with sailing directions for the principal ports and harbours of Europe, N. America, N. Africa, and the N. Atlantic Islands, etc. (London 1869, reprint London 2011)

Trakadas, A., Fish-salting in the northwest Maghreb in antiquity: a gazetteer of sites and resources (Oxford 2015): 54–57

Trakadas, A., ‘In Mauretaniae maritimis’: marine resource exploitation in a Roman North African province (Stuttgart 2018): 129–152

UNESCO, n.d. Medina of Essaouira (formerly Mogador). (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/753/, accessed 7/2020)

Thanks, such an interesting read. I have never been to the Mogador islands. Is it possible to embark there?